Copyright is a form of intellectual property that grants exclusive rights to creators over their original works of authorship, such as books, music, paintings, software, blog posts, and more. It protects the expression of ideas not the ideas themselves as soon as the work is fixed in a tangible medium, meaning it is captured in a form that can be seen, heard, or reproduced (like written, recorded, or saved digitally).

For a work to qualify for copyright protection, it must be original independently created by a human author with at least a minimal degree of creativity and fixed, so that it lasts more than a short time in some physical or digital form. However, certain things like names, titles, slogans, and common symbols are not protected by copyright.

Copyright is essential for creators and users alike, as it safeguards creative efforts, prevents unauthorized use, and encourages innovation by ensuring that creators can control how their work is used and monetized under the Copyright Act.

Evolution of Copyright in India

The concept of copyright in India has evolved significantly over time. It traces its roots back to 1847, during the rule of the East India Company, when the first copyright law was introduced.

At that time, copyright protection was not automatic authors had to register their works with the Home Office to enforce their rights, and the protection lasted for the author's lifetime plus seven years posthumously.

A major development occurred in 1914 with the introduction of a new copyright law that expanded the definition of copyright to a "sole right", granting authors exclusive control over reproduction, modification, and translation of their works. Additionally, criminal sanctions were introduced for copyright infringement. This 1914 law, largely influenced by British copyright legislation, remained in force until India’s independence, after which the Copyright Act of 1957 was enacted. This new law replaced the colonial-era rules and laid the foundation for modern copyright protection in India.

Further advancement came in 2012 with the passage of the Copyright Amendment Bill, 2012, aimed at aligning Indian law with international standards, particularly the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT). Key changes included updated rights for artistic works, films, and sound recordings, clearer provisions for licensing and assignments, and stronger protections against online piracy. Together, these legislative milestones reflect India's commitment to protecting creative works and promoting intellectual property rights in line with global standards.

Types of Copyright Protection

Copyright law extends protection to a broad range of creative expressions, each categorized based on the nature of the work. These categories ensure that creators retain legal control over the use, reproduction, and dissemination of their original content. The major types of copyright include:

-

Musical Works: This category safeguards original musical compositions, including melodies and arrangements, but does not cover the actual sound recordings. The copyright holder of a musical work has the exclusive rights to reproduce, perform publicly, and authorize others to use the composition.

-

Artistic Works: Visual art forms such as paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures, and architectural drawings fall under this category. Copyright grants the artist the right to display, reproduce, and distribute their works, thus protecting them from unauthorized use or copying.

-

Computer Software: This includes computer programs, source code, object code, and user interfaces. Software copyright enables developers to prevent the unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or modification of their programs, thereby protecting both the functionality and structure of the code.

-

Choreographic Works: Dance routines and choreographed performances are also subject to copyright protection. These rights allow creators to reproduce, record, and publicly perform their choreography, as long as it is sufficiently fixed in a tangible form such as video recordings or written notation.

-

Dramatic Works: These include scripts, plays, and theatrical performances intended for live presentation. While they may include some elements of movement or speech, they are distinct from cinematographic works and enjoy protection over performance rights, adaptation, and publication.

-

Cinematographic Films: This category pertains to motion pictures, videos, and film recordings that are presented as moving images. Copyright gives the filmmaker or producer the rights to distribute, screen publicly, adapt, and license the work.

-

Literary Works: One of the most common categories, literary copyright applies to written material such as novels, poems, scripts, articles, manuals, and even computer code. Authors hold the exclusive rights to reproduce, publish, translate, and adapt these works into different formats or media.

-

Sound Recordings: Separate from musical compositions, this refers to the actual recorded performance of music, speech, or other sounds. The copyright owner controls how the audio content is reproduced, distributed, or used to create derivative works.

-

Architectural Works: This type of copyright protects the designs and blueprints of buildings and structures, including the architectural plans and the physical appearance of completed buildings. It restricts unauthorized copying, construction, or modification of the design.

-

Compilations and Databases: Collections of data or selected works, such as encyclopedias, anthologies, and structured databases, are protected for the original arrangement, selection, and coordination of content even if the individual items are not copyrighted themselves. This helps ensure the integrity of the compilation as a whole.

Who Owns a Copyright?

Under Indian law and in most jurisdictions the first owner of a copyright is normally the human creator who fixes an original work in a tangible form, whether that is snapping a photograph, writing source code, sculpting a statue, or recording a song. Section 17 of the Copyright Act,1957 enshrines this principle but then lists important exceptions and special cases:

Works Made for Hire / Employment

-

Employees: When an employee produces a work “in the course of employment,” the employer becomes the first owner unless the employment contract says otherwise.

-

Partnerships & Firms: A partner who drafts material while acting for the firm creates copyright that vests in the partnership.

Commissioned or Contracted Works

-

Copyright can shift by contract. An independent contractor’s commission agreement or an explicit assignment can stipulate that the commissioning party or anyone else will be the first or subsequent owner.

Specific Categories under Section 17

-

Literary, musical, artistic, dramatic works (e.g., novels, speeches, paintings, dance notation): the author/artist is the first owner.

-

Cinematograph films: the producer (the person who finances and coordinates production) is deemed the first owner, although lyricists, composers, scriptwriters, etc., retain separate copyrights in their underlying contributions.

-

Sound recordings: again, the producer is treated as first owner.

-

Architectural works: the architect/creator owns the design unless contractually assigned.

-

Public speeches: the speaker owns the copyright in the spoken text, even if someone else organized the event.

Transfers After Creation

-

Ownership can later pass by assignment, licence, sale, will, or any other valid transfer. Businesses routinely buy or license copyrights, meaning a company or individual who did not create the work can become the new copyright owner.

Because copyright vests automatically at the moment of fixation, everyone who creates an original work is instantly a copyright owner, but understanding these statutory exceptions and documenting any contractual transfers is essential to avoid later disputes and to secure the legal and commercial value of creative assets.

What is Copyright Registration?

Copyright registration is the process of officially recording a creative work with the Copyright Office, providing creators with enhanced legal protection beyond the automatic rights that arise upon creation. In India, registration is voluntary but highly beneficial under the Copyright Act, 1957. Once registered with the Copyright Office of India, a public record of ownership is created, which can be vital in proving rights during infringement disputes. Registration enables creators to seek statutory damages, injunctions, and legal fees in court, and also serves as prima facie evidence of ownership and originality.

Although copyright arises automatically once an original work is fixed, registration strengthens enforcement, especially when ownership is contested. It also benefits the public by making ownership information accessible, supporting licensing, and offering notice that a work is protected.

In India, the Copyright Office provides an online platform for filing applications, examining claims, and issuing registration certificates. A copyright search is strongly recommended before claiming or transferring ownership to avoid conflicts.

In contrast, in the United States, registration is mandatory for enforcement through litigation, and must be done through the U.S. Copyright Office. While the legal frameworks differ, both systems emphasize the importance of registration in protecting creative rights and promoting a structured approach to intellectual property.

Assignment and license under copyright

Assignment of Copyright

An assignment of copyright is a legal transfer of ownership from the original copyright holder (known as the assignor) to another person or entity (called the assignee). In this process, the assignor sells or transfers some or all of their rights under a formal agreement. Once assigned, the assignee becomes the new copyright owner for the rights specified in the agreement and can use, reproduce, or exploit the work in any manner they choose without needing further permission from the original creator.

Under Section 18 and 19 of the Copyright Act, 1957, an assignment:

-

Must be in writing and signed by both parties.

-

Should clearly state the work, rights assigned, duration, and territory.

-

If any of these details are missing, the Act presumes the assignment to be for 5 years and applicable only within India.

Once the assignment is complete, the original owner loses control over the assigned rights.

Example: An author sells all publishing rights of a novel to a publishing house through an assignment deed. The publisher becomes the new rights holder and can publish, sell, or adapt the work as per the agreement.

License of Copyright

A license of copyright is a permission granted by the copyright owner (licensor) to another person (licensee) to use certain rights of the work without transferring ownership. In this arrangement, the copyright holder retains their ownership but permits limited usage of the work under specific terms and conditions.

A copyright license:

-

Can be written, oral, or even implied from conduct or circumstances.

-

Can be exclusive, non-exclusive, or sole, depending on how many parties are allowed to use the work.

-

Allows the licensor to continue using or licensing the same work to others (unless it’s an exclusive license).

-

Can include conditions like license fees, usage limits, duration, and territorial scope.

Licensing is usually preferred over assignment when the creator wants to retain control and earn recurring income through multiple users.

Example: A software developer grants users a license to use the program through an End User License Agreement (EULA). The users can use the software as specified, but the developer keeps ownership.

Assignment vs Licence of Copyright

Under the Copyright Act,1957, copyright is treated like any other movable property: it can be transferred either entirely by assignment or partially by licence.

|

Aspect |

Assignment |

Licence |

|

Nature of transfer |

Complete transfer (“sale”) of the specified rights. The assignor permanently parts with those rights; the assignee steps into the shoes of the owner. |

Owner (licensor) retains title but authorises a licensee to exercise one or more specific rights (e.g., reproduction, public communication) without infringing copyright. |

|

Formality required |

Must be in writing and signed by both parties (s.19). It must spell out the exact work, rights, territory, and term; otherwise the Act supplies default limits (five year term, India only territory). |

May be written, oral, or implied from conduct (though exclusive licences should be written to avoid disputes). |

|

Control after transfer |

Assignor loses control; assignee can exploit the work as they wish, unless the deed reserves rights. |

Licensor keeps overall control and can impose conditions (scope, duration, territory, royalties, quality control, etc.). |

|

Typical use cases |

Book publisher buying all publishing rights; producer acquiring film remake rights. |

Software EULAs, music streaming permissions, merchandising deals, academic photocopy permissions. |

|

Revocation / termination |

Only by mutual agreement or as provided in the deed (or statutory reversion after 25 years for literary/dramatic/musical works if author is the assignor). |

Usually ends automatically on expiry of the agreed term or breach of conditions; can be revoked according to contract or by the author after five years if licence is unexercised (s.30A). |

Why licences are often preferred:

-

The creator keeps ownership and can grant multiple overlapping licences, maximising revenue streams.

-

They allow finer commercial control (e.g., different licence fees for streaming, download, public performance).

-

Flexibility: a licence can be tailored for territory, medium, or time, whereas an outright assignment severs ownership in one stroke.

The duration of copyright protection

The duration of copyright protection varies depending on the type of creative work and the legal jurisdiction in question. Under Indian copyright law, the period of protection is generally quite extensive to ensure that both the creator and their legal heirs benefit from the rights associated with the work. The following is a detailed overview:

-

Literary, Dramatic, Musical, and Artistic Works: These categories of works are protected for the entire lifetime of the author, and the copyright continues for an additional 60 years after their death. This extended period ensures that the author’s estate can continue to benefit from the work long after the author has passed away. The 60-year term is calculated from the beginning of the calendar year following the year in which the author dies.

-

Cinematographic Films: In the case of films, the copyright is not tied to the life of the creator but instead is valid for 60 years from the year in which the film was first published or released. This means that regardless of whether the filmmaker is alive or deceased, the protection begins from the date the public first had access to the film.

-

Sound Recordings: Similar to films, sound recordings are protected for a fixed term of 60 years from the year they are first made available to the public. This ensures that the producers and rights holders can commercially exploit the recordings for several decades.

This framework aims to balance the rights of creators and the public, allowing sufficient time for creators and their families to benefit from their work while eventually making the work available for public use.

Procedure for Obtaining Copyright in India

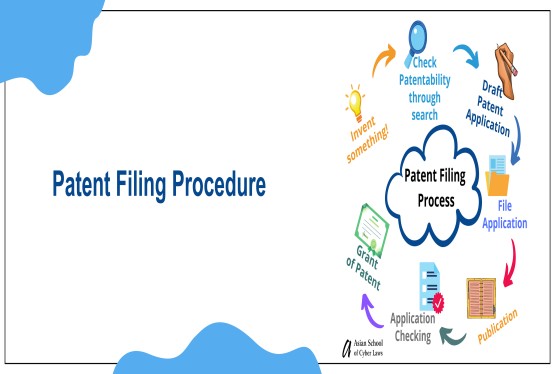

To secure copyright protection, an applicant must follow a structured process as outlined under the Indian Copyright Act. This procedure is applicable to both published and unpublished works. The key steps are as follows:

Filing the Application

The applicant must submit a copyright application in the prescribed format, along with the requisite fee. The payment can be made through a Demand Draft (DD) or Indian Postal Order (IPO).

Issuance of Diary Number

Once the application is submitted, a diary number is generated and issued to the applicant as a reference for future correspondence and tracking.

Mandatory Waiting Period (30 Days)

A statutory waiting period of 30 days follows the issuance of the diary number, during which any person may raise objections to the registration of the work.

In Case No Objection is Raised

-

The application proceeds for examination.

-

A copyright examiner reviews the application to identify any discrepancies or deficiencies.

-

If no issues are found, the application is forwarded for final approval.

-

If discrepancies are detected, a discrepancy letter is issued to the applicant. The applicant is then allowed to submit a response.

-

The Registrar of Copyrights will evaluate the response. If satisfied, the application is approved, and an extract from the Copyright Register is provided to the applicant.

-

If the registrar is not satisfied with the reply, the application may be rejected, and a rejection letter is issued accordingly.

In Case an Objection is Filed

-

Notification letters are sent to both parties the applicant and the objector.

-

Both parties are given an opportunity to submit their replies.

-

The Registrar conducts a hearing, where the submissions of both sides are considered.

-

If the objection is found to be invalid, the application proceeds for approval.

-

If the objection is upheld, the application will be rejected.

This systematic process ensures a fair and transparent mechanism for the grant of copyright, balancing the rights of creators with the interests of the public and other stakeholders.

Infringement of Copyright

Copyright infringement occurs when a person unlawfully uses a work that is protected under copyright law without obtaining prior permission from the rightful owner. This may include unauthorized use or reproduction of various forms of creative content such as the theme of a book, a written article, song lyrics, artwork, or any other original expression.

Once a work is protected by copyright, it cannot be legally reproduced, distributed, shared, or made accessible to the public whether in digital format or through any other medium without the explicit authorization of the copyright holder. The copyright owner may be an individual, such as the creator, or a legal entity like a publishing house or company that holds the rights.

Unauthorized use not only violates the exclusive rights of the creator but may also lead to legal consequences under the Copyright Act. Therefore, it is essential to respect copyright protections and seek appropriate licenses or permissions before using copyrighted material.

Remedies for Copyright Infringement

When copyright is violated, the law provides various remedies to safeguard the rights of the copyright holder. These remedies are broadly categorized into civil, criminal, and administrative measures:

Civil Remedies

In civil proceedings, the copyright owner can seek relief through the courts. The primary civil remedies include:

-

Injunction: A court order to stop the infringing activity immediately.

-

Account of Profits: A demand that the infringer disclose and return any profits earned through the unauthorized use of the copyrighted work.

-

Delivery Up: The infringing copies may be ordered to be handed over to the rightful owner or destroyed.

-

Damages: Compensation for the financial loss suffered due to the infringement, which may also include conversion damages.

Criminal Remedies

In cases of willful infringement, criminal proceedings can be initiated. These remedies serve as a deterrent and include:

-

Imprisonment: The infringer may face a jail term.

-

Fine: A monetary penalty may be imposed.

-

Both: In some cases, the court may order both imprisonment and fine depending on the severity of the offense.

Administrative Remedies

Administrative relief can be sought by approaching the Registrar of Copyrights. This is particularly useful in cases involving importation of infringing goods. The available actions include:

-

Prohibiting Import: Requesting the Registrar to ban the import of infringing copies into India.

-

Seizure and Delivery: The infringing copies can be seized and handed over to the copyright owner.

These remedies collectively aim to enforce copyright law, protect creators’ rights, and prevent unlawful exploitation of intellectual property.

Conclusion

Copyright is a vital component of Intellectual Property Rights, offering creators legal protection and control over their original works. In India, copyright arises automatically upon the creation of an original, fixed work and extends for the lifetime of the author plus 60 years (or 60 years from publication for certain works like films and sound recordings).

The legal framework has evolved significantly from colonial-era laws to modern amendments aligned with international treaties. Creators can transfer rights through assignment or licence, and while registration is optional, it strengthens enforcement.

Infringement of copyright can lead to civil, criminal, and administrative remedies. Copyright helps protect creative efforts, encourages innovation, and ensures fair use. A well-informed approach benefits both creators and users, promoting a balanced and sustainable creative ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What is copyright?

Ans. Copyright is a legal right that protects the original works of authorship such as books, music, films, software, paintings, and more. It grants the creator exclusive rights to use, reproduce, distribute, and license the work.

Q2. Is copyright automatic in India?

Ans. Yes, copyright protection arises automatically as soon as an original work is created and fixed in a tangible form (written, recorded, saved digitally, etc.). Registration is not mandatory, but it is recommended for legal evidence.

Q3. What types of works are protected by copyright?

Ans. Copyright in India protects:

-

Literary works (including software and computer code)

-

Artistic works

-

Musical works

-

Sound recordings

-

Cinematographic films

-

Dramatic works

-

Architectural designs

-

Choreographic works

-

Compilations and databases

Q4. How long does copyright protection last in India?

Ans. Literary, musical, artistic, and dramatic works: Lifetime of the author + 60 years

-

Cinematographic films and sound recordings: 60 years from the date of publication

Q5. How do I register a copyright in India?

Ans. You can file an application online or physically with the Copyright Office along with the required fee. After scrutiny and a 30-day waiting period for objections, the work is examined and, if approved, registered.

Q6. Who owns the copyright in a work created during employment?

Ans. Generally, the employer is the first owner if the work is created during the course of employment, unless otherwise agreed by contract.

Q7. Can copyright be transferred or sold?

Ans. Yes. Copyright can be transferred through assignment (complete or partial transfer of rights) or licensing (granting permission to use without transferring ownership).

Q8. What is the difference between an assignment and a license?

Ans. Assignment: Transfers ownership of the rights to another party.

-

License: Grants permission to use the work without transferring ownership.

Q9. What constitutes copyright infringement?

Ans. Using, copying, distributing, or publicly displaying a copyrighted work without permission from the copyright owner constitutes infringement and can result in legal consequences.

Q10. What remedies are available for copyright infringement in India?

Ans. Remedies include:

-

Civil: Injunction, damages, account of profits

-

Criminal: Imprisonment and/or fine

-

Administrative: Ban on import of infringing copies through the Copyright Office

Q11. Can ideas be copyrighted?

Ans. No. Copyright protects only the expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves.

Q12. Is registration mandatory for enforcement in court?

Ans. While not mandatory in India, registration is advisable as it serves as prima facie evidence in court in case of infringement disputes.

_(b)_of_the_Trademark_Act,_1999_(1)_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)