Before diving into this legal battle, it is important to understand two key concepts: trademarks and copyrights. A trademark is a brand identifier, such as a name, logo, symbol, or design that distinguishes one business’s goods or services from another’s. For example, it’s the McDonald’s golden arches or the Nike swoosh. When one registers a trademark, one gain exclusive rights to use it in connection with specific products or services, preventing others from creating confusion in the marketplace. Copyright, on the other hand, protects original creative works like books, music, paintings, and artistic designs.

In this case, the artistic logo design of ‘DAKSHIN’ falls under copyright protection. While trademark law focuses on preventing consumer confusion and protecting brand identity, copyright law protects the creative expression itself. Both these intellectual property rights were at the heart of a recent legal showdown between two hospitality giants over the name “DAKSHIN,” a popular South Indian restaurant brand.

ITC Limited stands as one of India’s most diversified conglomerates with a storied history spanning over a century. Originally established as the Imperial Tobacco Company of India Limited in 1910, ITC has evolved into a multi-business enterprise with presence in Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG), hotels, packaging, paperboards, and agribusiness. The company’s hotel division, now operated through ITC Hotels Limited (the second plaintiff in this case), stands for one of India’s largest luxury hotel chains.

ITC Hotels runs multiple brands catering to different market segments, from the ultra-luxury ITC Grand to the upscale Welcomhotel brand. The company takes immense pride in its hospitality standards and brand reputation, cultivated over decades through consistent quality and service excellence. DAKSHIN restaurants hold special significance as premium South Indian cuisine destinations located within various ITC hotels across major Indian cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad.

According to ITC’s claims, the DAKSHIN brand generates substantial revenue, approximately Rs. 12.38 crores annually from its restaurants in 2023-24 alone. The company has invested heavily in marketing these restaurants through social media, e-commerce platforms, and traditional advertising, building what it considers significant goodwill and brand recognition nationwide.

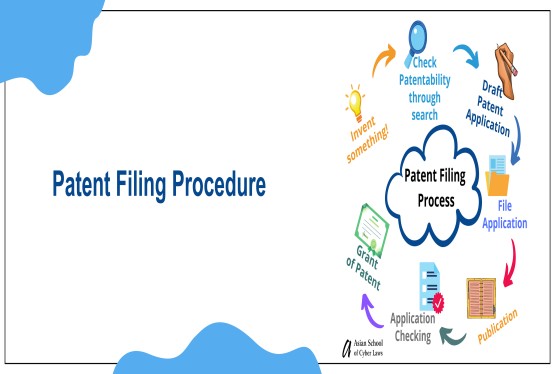

Background of the Case

The story dates way back to 1985, when ITC Limited (then plaintiff no.1) entered into an “Operating Services Agreement” with Adyar Gate Hotels Limited (the defendant), a Chennai-based company that owned hotel properties. Under this agreement, Adyar Gate owned the physical property, while ITC provided management services, operating the hotel under the brand name “Welcomgroup Park Sheraton Hotel” in Chennai.

Four years into this partnership, in 1989, the parties conceptualized a South Indian specialty restaurant within the hotel premises. After market surveys and consultation with an advertising agency (Hindustan Thompson Associates), the name “DAKSHIN” was chosen, and the restaurant opened on April 14, 1989. This restaurant became highly successful, receiving awards and recognition from prominent personalities. The collaboration continued smoothly for over two decades. During this period, ITC also opened DAKSHIN restaurants in its own wholly owned hotels in other cities. Such as, Hyderabad (1996), Delhi (2002), Mumbai (2005), and Bangalore (1999). In 1997, ITC even entered another similar operating agreement with Adyar Gate for a property in Visakhapatnam, where another DAKSHIN restaurant was established.

The relationship began to unravel in 2015 when the Operating Services Agreement for the Chennai hotel expired. ITC withdrew from managing the property, and Adyar Gate partnered with a different hotel operator, InterContinental Hotel Chain, an ITC competitor. The hotel was renamed “Crowne Plaza Chennai Adyar Park,” but the DAKSHIN restaurant continued operating at the same location. Notably, ITC did not object to this continued use of the DAKSHIN name.

The Chennai hotel eventually ceased operations on December 31, 2023, and the building was demolished to make way for a luxury apartment complex. However, in October 2024, Adyar Gate launched a standalone DAKSHIN restaurant at a new location in Chennai, that was no longer within any hotel, but as an independent dining establishment.

This move prompted ITC to file a lawsuit in February 2025, seeking to restrain Adyar Gate from using the DAKSHIN name, claiming trademark infringement, copyright violation, and passing off, meaning misleading consumers into thinking one business is associated with another.

Arguments Presented by the Petitioner

ITC’s legal team, led by senior advocates Mukul Rohatgi and Arvind Nigam, presented a strategic and intricate argument. ITC claimed to be the rightful owner of the DAKSHIN trademark, having obtained registrations dating back to September 2000, initially applied for on a “proposed to be used” basis and later amended to claim use since April 1, 1989. ITC also possessed a copyright registration dated November 15, 1989, for the artistic logo of DAKSHIN.

ITC argued that Article XIII of the Operating Services Agreement clearly established that all trademarks, trade names, and intellectual property belonged exclusively to ITC. Adyar Gate was merely granted a limited license to use these marks during the agreement period, which expired in 2015. After expiry, Adyar Gate had no right to continue using the DAKSHIN name.

And in order to justify filing the case in Delhi High Court (rather than Chennai where the restaurant operates), ITC argued that Adyar Gate’s restaurant is listed on e-commerce platforms like Zomato, EazyDiner, and social media, which are accessible in Delhi, thus soliciting customers nationwide The “dynamic effect” of Adyar Gate’s activities causes injury to ITC’s reputation in Delhi, where ITC operates its own DAKSHIN restaurant. The petitioner tries hard to show that there exists a reasonable apprehension that Adyar Gate might expand operations to Delhi, Under Sections 134 of the Trademarks Act and 62 of the Copyright Act, since ITC operates restaurants in Delhi, the Delhi High Court has jurisdiction.

ITC emphasized its substantial investment in building the DAKSHIN brand across India, with multiple locations, significant revenue generation, extensive social media presence, and numerous awards and recognitions. ITC contended there was no delay in filing the suit because, business relationships continued until 2019 (for the Visakhapatnam property), the COVID-19 pandemic affected operations until 2022, the Chennai hotel ceased operations in 2023, and the standalone restaurant only opened in October 2024.

Counter Arguments Presented by the Defendant

Adyar Gate’s defense, presented by senior advocates Rajiv Nayyar and Amit Sibal, came up with equally strong counter. First the the defendant argued that Delhi High Court lacked jurisdiction because, the restaurant operates solely in Chennai with no physical presence in Delhi and merely being listed on e-commerce platforms doesn’t constitute “targeting” Delhi customers, as actual commercial transactions (dining) occur only in Chennai. Establishing that Reservations made online are not completed transactions—customers must physically visit Chennai to dine, and no evidence exists of any intention to expand to Delhi, having operated exclusively in Chennai for over 30 years.

Adyar Gate claimed it was the true originator of the DAKSHIN concept. The defendant provided evidence showing, Mr. TT Vasu, Adyar Gate’s Chairman, conceived the idea after extensive market research. Adyar Gate hired the advertising agency and paid for all development costs. The Defandant provided its own annual report for 1988-89 showed the restaurant by them. Adyar Gate applied for trademark registration in 1990 (later abandoned) and successfully registered in 2004, claiming use since April 14, 1989

Since both parties hold valid trademark registrations in Class 42 (restaurant services) with similar user dates (both claiming April 1989), Adyar Gate argued they are “honest concurrent users” under Section 12 of the Trademarks Act. Section 28(3) protects such concurrent registrations, hence neither party can sue the other for infringement without first challenging the validity of the other’s registration.

Adyar Gate pointed out that ITC stood by silently for nearly a decade (2015-2025) while Adyar Gate continued using the DAKSHIN name, even in partnership with ITC’s competitor. Under Section 33 of the Trademarks Act, if a trademark owner remains silent while aware of infringement, for five continuous years, they lose the right to challenge that use. ITC’s failure to object constitutes acquiescence.

The defendant provided invoices, turnover certificates, and operational documents showing Adyar Gate was the entity running the DAKSHIN restaurant, collecting revenues, and managing operations throughout the collaboration period and afterward.

Adyar Gate argued that since it genuinely conceived, developed, and operated the DAKSHIN restaurant since 1989, there was no “passing off”, that is no attempt to mislead consumers into thinking the restaurant was associated with ITC.

The Observation and Analysis Made by the Court

Justice Amit Bansal of the Delhi High Court delivered a comprehensive judgment that analyzed each argument presented by both parties. The Court extensively examined whether Delhi High Court had the authority to hear this case. Citing the Supreme Court judgment in Asma Lateef v. Shabbir Ahmad (2024), Justice Bansal noted that even while considering interim relief, courts must form at least a prima facie view on jurisdiction. The Court rejected ITC’s argument about e-commerce platform listings, following the Division Bench judgment in Banyan Tree Holding (P) Limited v. A. Murali Krishna Reddy (2009). This precedent established that mere accessibility of a website does not confer jurisdiction, there must be “intentional targeting” and actual commercial transactions completing within the forum state’s jurisdiction.

Justice Bansal observed: “Even though a reservation/booking can be made through an e-commerce website, the person would have to visit the restaurant to avail its services and conclude a commercial transaction.” Since dining occurs in Chennai, no commercial transaction happens in Delhi, and therefore, no cause of action arises in Delhi.

The Court similarly dismissed the “dynamic effect” argument. ITC claimed that negative reviews of Adyar Gate’s Chennai restaurant would harm ITC’s Delhi restaurant’s reputation. However, Justice Bansal found this baseless, noting that ITC provided no evidence of any customer actually confusing the two restaurants or of any actual harm to ITC’s Delhi operations.

On the “quia timet” action (lawsuit based on apprehension of future infringement), the Court cited New Life Laboratories Private Limited v. DR Ilyas and held that mere speculation isn’t enough—there must be “tangible or reasonable material” supporting the fear of expansion to Delhi. Given that Adyar Gate operated exclusively in Chennai for over 30 years with no presence elsewhere, this apprehension was found to be baseless.

Regarding jurisdiction under Sections 134 (Trademarks Act) and 62 (Copyright Act), the Court applied the Supreme Court’s reasoning from Indian Performing Rights Society Ltd. v. Sanjay Dalia (2015). Since ITC’s registered office is in Kolkata and the cause of action arose in Chennai, merely having a subordinate office in Delhi doesn’t confer jurisdiction on Delhi High Court.

Even after finding lack of jurisdiction, Justice Bansal proceeded to analyze the substantive claims, noting that extensive arguments had been made on merits. The Court noted that both parties hold valid trademark registrations for “DAKSHIN” in Class 42 (restaurant services), both claiming user since April 1989. Under Section 28(3) of the Trademarks Act, when two parties hold registrations for identical or similar marks, neither can sue the other for infringement unless the opposing registration is first declared invalid.

Justice Bansal observed: “Therefore, in my prima facie view, a case for infringement cannot be made out and the present case has to be adjudicated on the principles of passing off.” The Court carefully examined Article XIII of the 1985 agreement, which ITC relied upon heavily. Justice Bansal concluded that this clause only referred to ITC’s existing trademarks. Since DAKSHIN didn’t exist in 1985 (created in 1989), it couldn’t have been covered by this clause.

Furthermore, the Court noted that the agreement was amended multiple times over the years, yet DAKSHIN was never added to any list of ITC’s proprietary marks. ITC also never communicated to Adyar Gate that DAKSHIN was ITC’s mark being licensed for use.

Therefore, who really Conceived DAKSHIN, became a critical factual question. The Court examined documents from both sides. Adyar Gate provided excerpts from published books, contemporaneous newspaper articles, annual reports, architectural plans, and conceptualization documents showing Mr. TT Vasu (Adyar Gate’s Chairman) conceived the restaurant after market research. The advertising agency HTA was hired and paid by Adyar Gate to develop the name. Adyar Gate provided invoices showing it collected restaurant revenues, had the FSSAI license, and operated the establishment.

The Court found: “On a prima facie analysis of the documents filed by the parties, I am of the view that the defendant was involved in conceptualization of a South Indian restaurant under the name of ‘DAKSHIN’ and was involved in running the same from 14th April 1989 till 31st December 2023.”

ITC presented a copyright registration certificate for the DAKSHIN logo. However, Justice Bansal distinguished between Sections 48 (Copyright Act) and 31 (Trademarks Act). While trademark registration creates a presumption of validity, copyright registration merely provides a weaker presumption that’s more easily rebutted. Critically, the copyright certificate showed the author as “Indu Balachandran, Hindustan Thompson” (the advertising agency employee). Under Section 17(1)(c) of the Copyright Act, when an employee creates a work in the course of employment, the employer (HTA) is the first owner of copyright—not the client (ITC). Since Adyar Gate hired and paid HTA, and ITC provided no evidence of commissioning the logo, the copyright claim failed.

For passing off, ITC needed to establish five elements from Ramdev Food Products (P) Ltd. v. Arvindbhai Rambhai Patel (2006), those are, Misrepresentation by the defendant, made in the course of trade, to prospective customers, calculated to injure the plaintiff’s business/goodwill and causing actual damage. Justice Bansal found the first element, misrepresentation, was not established. Since Adyar Gate genuinely conceived and operated DAKSHIN since 1989, it was not trying to “pass off” its restaurant as ITC’s. The defendant had acquired its own goodwill and reputation in Chennai through continuous use. Crucially, ITC provided no evidence of actual confusion, no customer complaints, no surveys, no instances of anyone mistaking Adyar Gate’s restaurant for ITCs.

Section 33 of the Trademarks Act states that if a trademark owner remains silent for five continuous years while aware of another’s use, they lose the right to challenge that use (unless the later registration was obtained in bad faith). The timeline was damning for ITC. In 2015, ITC exits the Chennai property; Adyar Gate continues using DAKSHIN with a competitor operator. In 2015-2023, Eight years of continuous use by Adyar Gate, with ITC’s full knowledge. In October 2024, Standalone restaurant opens. On February 2025, ITC finally files suit, ten years after the partnership ended. The Court cited Intex Technologies (India) v. M/s. AZ Tech (India) (2017) and Rhizome Distilleries v. Pernod Ricard S.A. France (2009), both holding that delay while a defendant builds substantial business defeats claims for interim injunction. Justice Bansal rejected ITC’s excuses for delay. The claim of “cordial relations” was contradicted by ITC’s own arbitration proceedings against Adyar Gate in 2017 over a different property. The COVID-19 pandemic excuse failed because ITC filed multiple other lawsuits during that period, showing it wasn’t unable to litigate.

The Court observed that it was evident that from the year 2016-17 till 2023-24, the defendant had developed sizeable turnover in respect of its restaurant running under the trademark ‘DAKSHIN.’ Therefore, it cannot be said that there was a cordial relationship between the plaintiffs and the defendant on account of which the plaintiffs did not object the defendant’s user of ‘DAKSHIN’ mark.

Finally, applying the principle from Wander Ltd. v. Antox India P. Ltd. (1990), the Court noted that interim injunctions aim to preserve the status quo. Since Adyar Gate had operated DAKSHIN continuously from 1989, including 1989-2015 jointly with ITC and 2015-2025 independently granting an injunction would disrupt the status quo rather than preserve it. The scales favoured Adyar Gate, shutting down its long-established restaurant would cause irreparable harm, whereas if ITC eventually wins at trial, monetary damages could compensate any proven losses.

Reasons Behinds the Courts Judgement

The court established that ITC attempted to litigate in Delhi for convenience, despite the restaurant being exclusively in Chennai. The e-commerce platform argument was legally insufficient under established precedents requiring actual commercial transactions within the forum jurisdiction. The court laid down that ITC’s claims of ownership crumbled under documentary scrutiny. The Operating Services Agreement didn’t explicitly grant ITC ownership of DAKSHIN, and Adyar Gate provided superior evidence of conception and operation.

The court stated that ITC’s copyright registration actually hurt its case by revealing that the advertising agency HTA created the logo, and Adyar Gate hired HTA—suggesting Adyar Gate, not ITC, commissioned the work. Also, the court reasoned that the ten-year gap between separation (2015) and lawsuit (2025) was fatal, especially given Adyar Gate’s substantial business development during this period. ITC’s explanations (cordial relations, pandemic) were unconvincing.

The court presented that both parties holding valid registrations with similar user dates created a legal stalemate. ITC should have filed a rectification petition challenging Adyar Gate’s registration before filing an infringement suit. The Court recognized the commercial reality: both parties jointly developed DAKSHIN as a collaboration, making it effectively a jointly conceived brand that both had legitimate claims to use.

The court ultimately established that ITC’s failure to provide any evidence of actual marketplace confusion, the cornerstone of trademark law was missing. Trademark rights exist to prevent consumer deception, but no deception was proven.

The Related Legal Provisions and Principles in the Case

Trademarks Act, 1999:

-

Section 12 (Honest Concurrent Use): Allows multiple parties to use similar marks if adoption was honest and concurrent

-

Section 28(3) (Rights of Concurrent Proprietors): When multiple parties hold registrations for identical/similar marks, exclusive rights are limited; infringement claims require first invalidating the opponent’s registration

-

Section 30(2)(e) (Statutory Defense): Use of a registered trademark that’s identical to another registered trademark doesn’t constitute infringement

-

Section 31 (Certificate of Registration as Prima Facie Evidence): Creates a presumption of trademark validity

-

Section 33 (Effect of Acquiescence): Five years’ acquiescence bars challenges unless bad faith is shown

-

Section 134 (Jurisdiction): Courts where the plaintiff resides/carries on business have jurisdiction, but interpreted narrowly per Sanjay Dalia principles

Copyright Act, 1957:

-

Section 17(1)(c) (First Ownership): In works created during employment, the employer is the first owner unless there’s a contract to the contrary

-

Section 48 (Certificate of Registration as Prima Facie Evidence): Provides only prima facie evidence of particulars, weaker than trademark registration presumption

-

Section 62 (Jurisdiction): Similar to Section 134 of Trademarks Act, but cause of action must meaningfully connect to forum

Relevant Case Laws

-

Asma Lateef v. Shabbir Ahmad, (2024) 4 SCC 696 - Supreme Court held that jurisdictional issues must be examined even at interim injunction stage; courts should record prima facie satisfaction on maintainability before granting interim relief

-

Indian Performing Rights Society Ltd. v. Sanjay Dalia, (2015) 10 SCC 161 - Supreme Court interpreted Sections 134 (Trademarks Act) and 62 (Copyright Act); held plaintiffs cannot file at far-flung subordinate office locations when cause of action and principal office are elsewhere; emphasized “convenience” rationale

-

S. Syed Mohideen v. P. Sulochana Bai, (2016) 2 SCC 683 - Supreme Court clarified that passing off actions remain available even when parties hold registered trademarks; registration doesn’t eliminate common law rights

-

Ramdev Food Products (P) Ltd. v. Arvindbhai Rambhai Patel, (2006) 8 SCC 726 - Supreme Court established the five-element test for passing off actions

-

Power Control Appliances v. Sumeet Machines, (1994) 2 SCC 448 - Supreme Court distinguished acquiescence from mere laches; acquiescence involves positive conduct inconsistent with exclusive rights claims; principle: one mark, one source, one proprietor

-

Wander Ltd. v. Antox India P. Ltd., 1990 Supp SCC 727 - Supreme Court held interim injunctions should preserve status quo; whether defendant has already commenced business is relevant to balance of convenience

-

Banyan Tree Holding (P) Limited v. A. Murali Krishna Reddy, 2009 SCC OnLine Del 3780 - Division Bench held mere website accessibility doesn’t confer jurisdiction; plaintiffs must show “targeting” through interactive websites enabling commercial transactions; overruled earlier “Casio” approach

-

Allied Blenders & Distillers v. R.K. Distilleries, 2017 SCC OnLine Del 7224 - Division Bench distinguished standards for Order VII Rule 10 (return of plaint) from Order XXXIX Rules 1&2 (interim injunction); defendants can challenge jurisdiction in interim applications even if plaint shouldn’t be returned

-

Impresario Entertainment & Hospitality v. S & D Hospitality, 2018 SCC OnLine Del 6392 - Single Judge held that merely enabling online reservations for a restaurant in another city doesn’t confer jurisdiction where reservations are made; actual commercial transaction (dining) must occur in forum

-

Tata sons v. Hakuna Matata, 2022 SCC OnLine Del 2968 - Division Bench held that where websites enable actual purchase of goods/services (cryptocurrency in that case), jurisdiction exists; distinguished from mere information websites

-

Ultra Homes Construction v. Purushottam Kumar Chaubey, 2016 SCC Online Del 376 - Division Bench applied Sanjay Dalia principles, creating a four-scenario framework for when plaintiffs can sue at subordinate office locations

-

Intex Technologies (India) v. M/s. AZ Tech (India), 2017 SCC OnLine Del 7392 - Division Bench denied interim injunction due to 14-month delay while defendant invested Rs. 200 crores and built substantial market presence

-

Rhizome Distilleries v. Pernod Ricard S.A. France, 2009 SCC OnLine Del 3361 - Division Bench held that delay and acquiescence while defendant’s sales increased manifold defeats interim injunction claims

-

Brihan Karan Sugar Syndicate v. Yashwantrao Mohite Krushna Sahakari Sakhar Karakhana, (2024) 2 SCC 577 - Supreme Court confirmed acquiescence is a complete defense in copyright infringement actions

-

Girdhari Lal Gupta v. M/s K. Gian Chand Jain & Co., 1977 SCC OnLine Del 146 - Full Bench introduced “dynamic effect” principle for design registration jurisdiction; effect of registration travels to places where registered goods sold

-

Dr. Reddy Laboratories Limited v. Fast Cure Pharma, 2023 SCC OnLine Del 5409 - Extended “dynamic effect” to online sales; rectification can be filed where goods bearing mark are available for purchase online

-

Cable News Network v. CTVN Calcutta Television Network, 2023 SCC Online Del 2436 - Summarized Banyan Tree principles into 10-point test for internet jurisdiction, emphasizing targeting and commercial transaction completion

Conclusion

The Delhi High Court’s decision in ITC Limited v. Adyar Gate Hotels Limited offers profound insights into the complexities of intellectual property rights when business relationships evolve and ultimately dissolve. This case underscores several critical lessons for businesses and legal practitioners alike.

First and foremost, the judgment reaffirms that trademark rights aren’t merely about who files registration first, but about genuine commercial origin, honest use, and actual marketplace dynamics. While ITC invested heavily in building the DAKSHIN brand across India and generates significant revenue from its restaurants, the Court recognized that Adyar Gate possessed an equally legitimate claim rooted in the brand’s original conception and three decades of continuous use in Chennai.

The case illuminates the dangers of legal complacency. ITC’s ten-year silence while Adyar Gate continued operating under the DAKSHIN name—including eight years after their partnership ended—proved legally fatal. In intellectual property law, vigilance isn’t merely advisable; it’s mandatory. Rights holders must actively police their marks, or risk losing the ability to enforce them through the doctrine of acquiescence. This doctrine serves an important policy purpose: preventing trademark owners from strategically waiting until a competitor has invested substantially before swooping in with litigation designed to destroy that investment.

The jurisdictional analysis carries broader implications for India’s increasingly digital economy. ITC’s argument that online platform listings confer nationwide jurisdiction was rejected, with the Court maintaining that actual commercial transactions—not mere online visibility—determine where legal battles can be fought. This preserves the fundamental principle that defendants shouldn’t be dragged into distant forums merely because information about them is accessible online. In an age where every business has a digital footprint, accepting ITC’s position would have made geographic jurisdiction virtually meaningless.

The judgment highlights the importance of clear contractual drafting. The Operating Services Agreement between ITC and Adyar Gate failed to explicitly address ownership of brands developed during the partnership, a costly omission. Article XIII referenced ITC’s existing trademarks but didn’t clearly cover future jointly developed brands like DAKSHIN. This ambiguity, combined with the commercial reality of joint conception and operation, created an ownership dispute that probably could have been avoided with more precise contractual language.

The case demonstrates judicial practicality in recognizing commercial realities over formalistic legal positions. The Court acknowledged that DAKSHIN was effectively a jointly conceived brand—born from a collaborative relationship where both parties contributed to its development and success. In such circumstances, rigid application of “one mark, one owner” principles would have been inequitable. The concurrent registration framework under the Trademarks Act accommodates exactly this situation, allowing both parties to use the mark in good faith.

For ITC, this represents a strategic setback but not necessarily a total loss. The judgment preserves its right to operate DAKSHIN restaurants outside Chennai, while Adyar Gate is bound not to expand beyond Chennai until final trial. If ITC eventually challenges Adyar Gate’s trademark registration through rectification proceedings and succeeds in proving bad faith or invalidity, it might still prevail. However, given the Court’s findings on evidence of conception and the acquiescence defense, such success appears unlikely. For Adyar Gate, the judgment validates its claim to a brand intrinsically linked to its business identity for over three decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Why did the Delhi High Court refuse to entertain ITC’s trademark infringement suit despite ITC having a registered trademark for “DAKSHIN”?

Ans. The Court held that when both parties possess valid trademark registrations with the same user date, Section 28(3) of the Trademarks Act applies. In such cases, exclusive infringement rights are diluted, and one registered proprietor cannot sue another for infringement unless the opposing registration is first invalidated through rectification proceedings.

Q2. Why did ITC’s copyright claim over the DAKSHIN logo fail?

Ans. Although ITC held a copyright registration, the Court found that the logo was created by an employee of Hindustan Thompson Associates (HTA). Under Section 17(1)(c) of the Copyright Act, the employer (HTA), not ITC, became the first owner. Since Adyar Gate had hired and paid HTA, ITC failed to prove ownership of the copyright.

Q3. Why did ITC’s copyright claim over the DAKSHIN logo fail?

Ans. Although ITC held a copyright registration, the Court found that the logo was created by an employee of Hindustan Thompson Associates (HTA). Under Section 17(1)(c) of the Copyright Act, the employer (HTA), not ITC, became the first owner. Since Adyar Gate had hired and paid HTA, ITC failed to prove ownership of the copyright.

Q4. If ITC eventually wins at trial, can Adyar Gate be forced to shut down its restaurant after operating for 35 years?

Ans. Practically, even if ITC were to succeed later, the Court has already indicated that monetary compensation, not shutdown, would be the appropriate remedy, because Adyar Gate’s long-standing operation and goodwill make injunctive relief inequitable and commercially destructive.

Q5. What role did delay, and acquiescence play in the Court’s refusal to grant an injunction?

Ans. ITC remained silent for nearly ten years after exiting the Chennai hotel in 2015 while Adyar Gate continued operating “DAKSHIN.” Under Section 33 of the Trademarks Act, such prolonged silence amounts to acquiescence, which bars enforcement, especially when the defendant has built substantial goodwill during that period.

Q6. Does the presence of a restaurant on platforms like Zomato, EazyDiner, or Instagram give courts across India jurisdiction?

Ans. No. The Court reaffirmed that mere online visibility or accessibility does not create jurisdiction. Jurisdiction arises only when there is intentional targeting of customers in the forum state and completion of commercial transactions there. Since dining occurs physically in Chennai, no cause of action arose in Delhi.

Q7. How did the Court distinguish between trademark infringement and passing off in this case?

Ans. Trademark infringement is a statutory remedy dependent on exclusive registration rights. Passing off is a common law remedy focused on misrepresentation and consumer confusion. Because infringement was barred due to concurrent registrations, the Court examined the case purely on passing off principles, where ITC failed to prove misrepresentation or confusion.

Q8. How did the doctrine of honest concurrent use under Section 12 of the Trademarks Act influence the Court’s decision?

Ans. Both parties possessed valid trademark registrations for “DAKSHIN” with similar user claims dating back to 1989. This brought the dispute within the framework of honest concurrent use, where neither party can assert exclusive infringement rights unless the other’s registration is first invalidated through rectification proceedings.

Q9. Why did the Court refuse to grant interim injunction even though ITC claimed nationwide reputation?

Ans. Applying Wander Ltd. v. Antox, the Court held that injunctions should preserve status quo. Since Adyar Gate had been operating “DAKSHIN” continuously for over three decades, stopping its operations would cause irreparable harm, whereas ITC could be compensated monetarily if it ultimately succeeded.

Q10. Can a brand born out of a joint business relationship ever be claimed exclusively by one party later?

Ans. Only if clear contractual terms, consistent conduct, and timely enforcement exist. This case shows that without explicit ownership clauses and vigilant protection, courts may treat such brands as jointly conceived commercial assets, limiting exclusive claims.

_(b)_of_the_Trademark_Act,_1999_(1)_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)

_crop10_thumb.jpg)